With Federal EV Incentives Vanishing, State EV Incentives Must Get Smarter

With Federal EV Incentives Vanishing, State EV Incentives Must Get Smarter

By Matthew Metz, July 14, 2025

With federal incentive programs for EVs ending, state EV programs must deliver greater gasoline displacement and household savings per dollar spent. The solution: focus outreach and spending on high-gasoline users who will see the greatest fuel savings. Here’s what states should do:

1. Use Data to Guide Outreach and Incentive Programs

State EV education and incentive programs have too often been designed for broad eligibility and minimal targeting. That approach may have been necessary in the early phases of the EV adoption curve, but not now when demand for EV incentives far exceeds supply. Today, states must ground their programs in hard data and target drivers for whom the transition to EVs will be most impactful.

That means using tools that estimate household gasoline use and fuel savings. As Coltura’s tools demonstrate, it's possible to identify and target the people for whom an EV will bring the greatest financial relief.

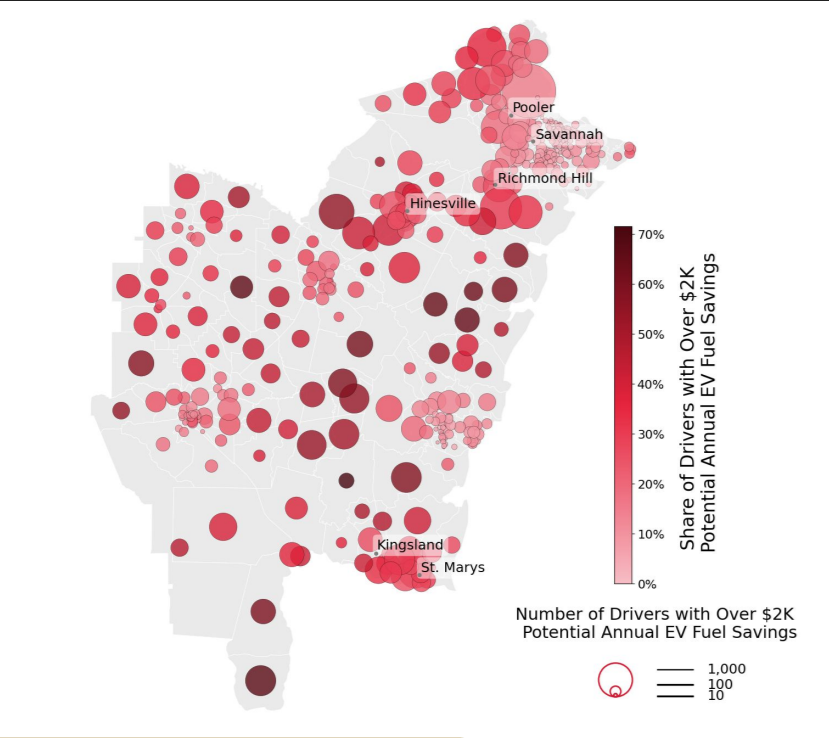

Map showing Georgia Congressional District 1 numbers and concentration of drivers who could save more than $2,000/year in fuel by switching to an EV.

2. Emphasize Fuel Savings as the Durable EV Advantage

Electric vehicles saved the average U.S. driver $943 in fuel costs in 2024. For drivers in the top 10% of mileage, savings reached an average of $2,721 annually. These cost advantages are meaningful, recurring, and predictable. And they’re strongest for the drivers who use the most gasoline. Those drivers are often low- to moderate-income people with long commutes, older vehicles, and limited access to transit. In many cases, high-mileage drivers will save thousands of dollars annually with an EV despite the elimination of federal subsidies. States should help these drivers calculate their individual savings potential and streamline their path to EV ownership.

State EV outreach and incentive programs should prioritize households for whom fuel savings will be transformative. Rather than offering a flat incentive to all persons below an income threshold, programs should steer support to the largest gasoline users. This will maximize gasoline reduction per dollar spent, keep more money in the pockets of the high-consumption households taking advantage of the benefit, and reduce carbon emissions more than an undifferentiated approach.

3. Measure What Matters and Adapt Based on Results

EV programs should maximize gasoline displacement per dollar spent while helping those who need it most. But most programs define success by rebates distributed, and ascribe carbon benefits based on the average gasoline use of the state’s drivers, missing opportunities to optimize performance. Smarter programs would track these key metrics based on actual program recipients and adjust in real-time:

- Gallons of gasoline displaced

- Annual fuel savings per participant

- Cost per gallon of gasoline displaced

- Equity outcomes (income, location, vehicle replaced)

Smart programs would also be more flexible, using these adaptive management strategies:

- Release funds in tranches rather than all at once

- Adjust incentive amounts if funds are depleting too quickly

- Redirect marketing if rebates aren't reaching high-gasoline users

- Modify eligibility based on early results

Washington State's recent experience illustrates the risk of inflexible design. The state's $45 million EV rebate program launched in August 2024 but exhausted its funding by October 2024—six months earlier than planned, and before any adaptation could occur. It did not measure gasoline displacement nor effectively target lower-income zip codes. Most of the money was expended in $9,000 incentives for three-year leases, providing only short-term benefits for those households. Could the state have incentivized twice as many people to buy EVs and tripled carbon reduction? We will never know because the program design lacked key metrics and the ability to adjust incentive levels or redirect efforts mid-program.

Programs that build in flexibility and learning can deliver far better results than those that simply distribute funds until they're gone.

4. Explore New Ways to Help With Upfront EV Costs

In addition to optimizing how subsidies are distributed, states and utilities should explore new ways to help with upfront costs. One promising model is offering down payment assistance in exchange for a share of the driver’s future fuel savings, similar to on-bill financing used for energy efficiency upgrades.

Under this model, an EV buyer might receive $3,000 advance toward a down payment, with a portion of their monthly fuel savings (which can exceed $200 for high-mileage drivers) allocated to repayment and added to their electric bill. This reduces the need for large grants, avoids burdening the buyer with new debt, and aligns repayment with actual savings. With thoughtful design, this approach can dramatically increase the reach of limited public funds while supporting lower-income, higher-gasoline drivers.

5. Conclusion

As federal dollars dry up, the EV movement can’t afford business as usual. We need smarter EV outreach and incentive programs, not just bigger ones. By focusing on fuel savings, measuring the outcomes that matter, and leveraging gasoline displacement as a financing tool, state programs can stretch their dollars further and build lasting momentum.

ARE YOU A MEDIA MEMBER, RESEARCHER OR INVOLVED IN POLICY-MAKING?

Get in touch with us with any questions or ideas!

LAST BUT NOT LEAST

Make sure you're signed up for our newsletter!

With news, resources and inspiration, it's a must-read for policymakers, researchers and activists interested in moving beyond gasoline.